Critical thinking

What is critical thinking?

- Being critical is not about ‘finding fault’ or making negative comments (Williams, 2014, p. viii)

- Instead, it is about ‘looking at ideas, theories and evidence with a questioning attitude … analyzing things in detail …deciding what you think and why’ (Godfrey, 2011, p. 17).

- Critical thinking is a skill you that can use in everyday life as well as at university.

How can I be critical?

- 1. Be truth-seeking

- We all have the potential for bias. A bias is a prejudice in favor of or against one thing.

- Aim to overturn previously held personal beliefs and be truth-seeking (Cohen, 2015).

- Watch the video below about personal beliefs and the ladder of inference.

2. Ask questions

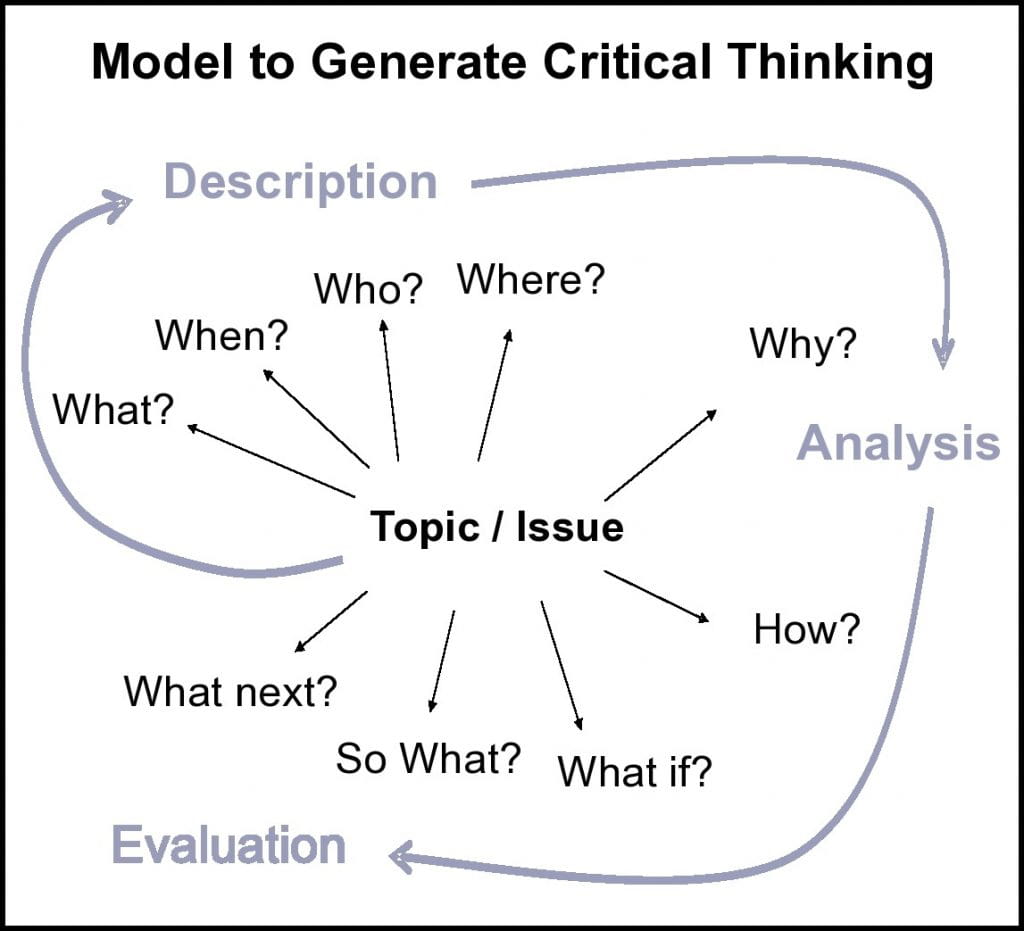

- Use the Plymouth University (2003) model below when thinking about topics or issues.

- Description provides context, outlines information and lists facts.

- Aim to move beyond the purely descriptive stage to evidence deeper thinking.

- Analysis explores key parts, interprets and makes links between information.

- Evaluation assesses worth and draws conclusions.

3. Include varied perspectives

- Aim to research information from a range of sources and perspectives.

- Perspectives might include practitioners, theorists (e.g. feminists), critics, journalists, historians, and industry experts.

- This aids triangulation, which involves using multiple methods or sources to fully understand a topic.

Critical thinking in reading

- Rather than accepting the information that you find, question a source’s reliability and usefulness.

- Use CRAAP test (this link opens in a new window) to review Currency, Reliability, Authority, Accuracy and Purpose.

- See examples of questions to ask below.

Questions to assess a source

What is the author trying to say?

What is the source’s purpose?

What evidence is used to support it?

How does the author use language?

How successfully is the argument presented? Any flaws?

(Adapted from Katz, 2018, p. 46)

- See more critical reading questions from Leeds University (2021).

Critical thinking in writing

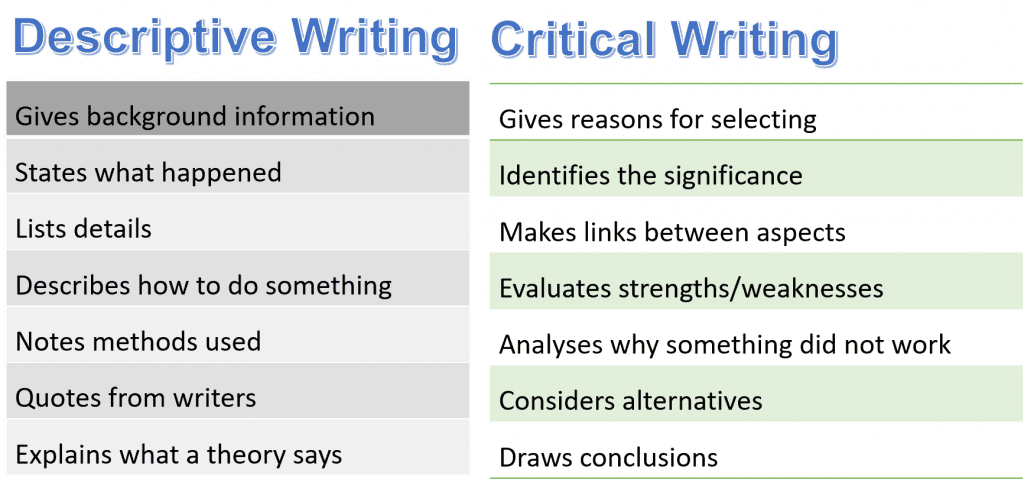

- Academic writing needs to feature a mixture of description and critical analysis.

- Descriptive writing: states, explains, notes, lists, gives information.

- Critical Analytical Writing: identifies the significance, evaluates strengths/weaknesses, weighs up sources against one another, argues a case, gives reasons for selecting, makes links between information, draws conclusions.

- See the PDF below for a full list of differences.

How might this look in writing?

- See an example of academic writing from a past essay below.

- Notice how small amounts of descriptive writing interweave with critical analysis highlighted in yellow.

- See more examples in the University of Birmingham’s (2015) Guide to Critical Writing below.

- Refer to the Study Skills page on paragraphs (this link opens in a new window) to view the structure of Point, Evidence, Comment, Conclude.

Example: Graphic Communication 3rd Year

Since the creation of Channel 4, the brand has set out to be ‘radically different… [and] provide innovative programming and cater for minority audiences not served by existing channels’ (Brown, 2007), suggesting that, in contrast to the BBC …, this channel already had very specific brand values set in place . It is clear to see by the initial branding, created by Lambie-Nairn, that the channel was breaking the boundaries, being playful and being exciting, something that the public had not really seen before from TV channels . The separate colourful interlocking blocks (fig 3.1), which form a number four, were fluidly used throughout the brand as a form of communication . The reasoning behind these blocks as the branding was due to ‘Lambie-Nairn [researching] Channel Four’s philosophy and [seizing] the fact that they would be buying all their programmes in, so Channel Four would be a patchwork’ (Barnes, 2016) as well as the movement of the blocks symbolising the “coming together”. This allowed the channel to have a personality, for example jokingly forming a number five (fig 3.2) rather than four, accompanied by a “malfunction” with the usual theme music, as the blocks come together. This humorous behaviour had not been seen through British channel branding before, which can only have made Channel 4 stand out even more, as the channel had found a gap within the market and focused their branding on this. The ethos of this branding has certainly been a huge success, as the foundation of the brand visuals have arguably remained virtually the same, aside from minor tweaks, from the launch in 1982, to present day.

Critical Writing Downloadable Examples Guide to Critical Writing (opens in a new window)Sources consulted

Cottrell, S. (2003) The study skills handbook. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Godfrey, J. (2011) Writing for university. Basinstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Leeds University (2021) Critical questions. Available at: Critical thinking questions | Library | University of Leeds (Accessed: 18 June 2021).

Plymouth University (2010) Critical thinking. Available at: www.plymouth.ac.uk/uploads/production/document/path/1/1710/Critical_Thinking.pdf (Accessed: 18 June 2021).

University of Birmingham (2015) Guide to critical writing. Available at: https://intranet.birmingham.ac.uk/as/libraryservices/library/asc/documents/public/pgtcriticalwriting.pdf (Accessed: 18 June 2021).

Williams, K. (2014) Getting critical. 2nd Edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.