Primary research

What is primary research?

- Primary research involves gathering information first-hand. It can help you generate information that’s up-to-date and specific to your research.

- It’s the opposite of secondary research, which is information gathered by others e.g. within published books or academic journals.

- Research methodology = the reasoning behind your approach to gathering data. Methodologies are based on ‘views, beliefs and values’ (Kara, 2015, p. 5).

- Some examples of methodologies include: action research (aims to bring about change or find solutions), practice-based (utilises your creative experimentations to form knowledge), autoethnography (includes personal observations/reflections in relation to the wider literature) or narrative enquiry (studying people’s experiences through stories).

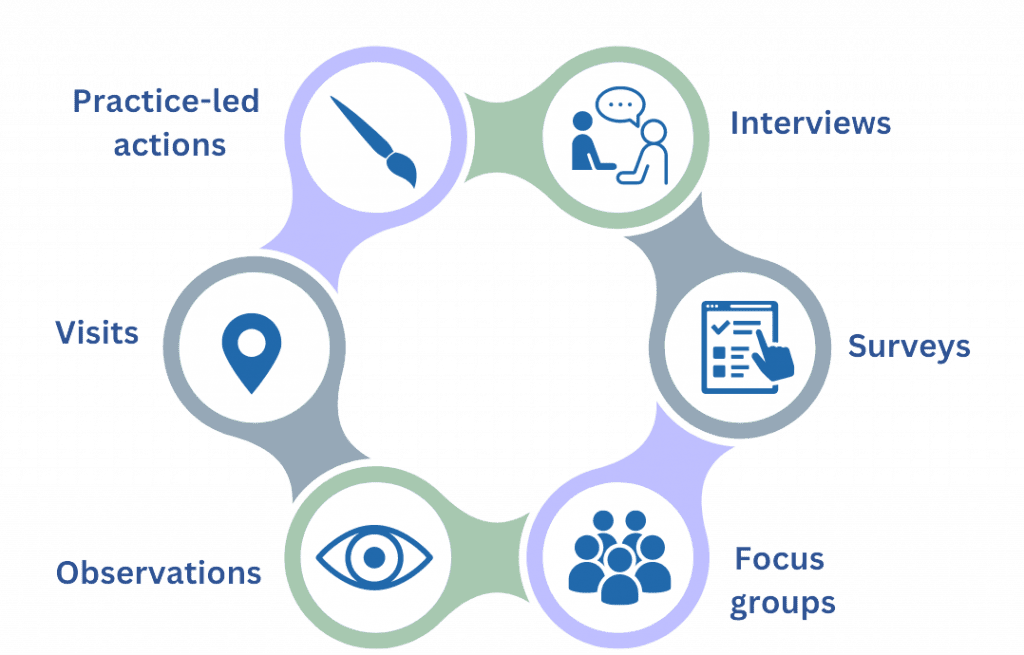

- Research methods = the tools you’ll use to collect the primary data e.g. interviews, surveys, focus groups or visits.

- Find definitions to key research collection terms in the SAGE research map: https://methods.sagepub.com/methods-map/qualitative-data-collection

How can I collect data?

Interviews:

- Structured interviews: questions are designed and asked in a set order.

- Semi-structured: organised around a set of core questions. However, there is flexibility to deviate, depending on where the conversation leads. This could include follow up questions e.g. ‘Can you tell me a bit more about …?’

Focus groups:

- Identify a group of relevant people (aim for around 6-8).

- Create a schedule of questions for your group to discuss. A typical order may include an opening, introductory questions, transfer questions, key questions, specific questions, closing questions (Krueger, 1998, p. 21).

- You can also use video, audio or visual prompts.

- Do not offer personal opinions or join in. This would lead to researcher bias.

- Remember to record the focus group for accurate transcripts. You’ll need their permission to do this (see informed consent).

Surveys:

- Try digital tools such as Microsoft Forms or Google Forms. Both do not place limits on how many responses can be viewed.

- Consider who you will ask (sample) and how you will promote it (e.g. via email, promotions online to relevant groups or networks).

- If you only collect a small sample size, it’s difficult to draw any reliable conclusions.

- Visits:

- This may include visiting relevant exhibitions, architectural spaces or businesses. Document your experiences through field notes (reflections that you capture at the time) and images.

- Archives: these contain primary sources such as written documents, photographs or textiles. Find a list of current archives via JISC: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/list/location

What are research ethics?

- Being ethical relates to ‘moral behaviour in research contexts’ (Wiles, 2013, p. 4).

- It includes following good practices for data collection, storage and use of information.

- The University’s code for ethics lists 6 key areas: respect (for your participants), honesty (in your approaches and conclusions), rigour (in project design), transparency and open communication (when sharing results and methods used), care for participants (e.g. through risk assessment or Health and Safety considerations) and care of self (your own wellbeing).

- You may need to gain permission to conduct your research if it involves sensitive topics, working with vulnerable adults or children.

- Complete the Norwich University of the Arts Ethics Checklist.

- If you answer ‘yes’ to any of the questions, you will need to complete the University’s Ethics Approval Form.

How do I approach participants?

- Firstly, spend some time considering who you’ll ask.

- There are different approaches for sampling, which Denscombe (2014) outlines. Purposeful sampling is where participants are picked due to relevance and/or knowledge. Snowball sampling is where participants refer others. One approach to be cautious about is convenience sampling where you ask those easy to access. If you’re asking family/friends, this can lead to bias because of your personal connection.

- Always inform participants who you are, what the project is about, why you are doing the research, what will be involved and what is happening to the information (Alderson, 1995, cited in Arksey and Knight, 1999, p. 69).

- Outline your research with introductory emails and participant information sheets.

- You should also obtain informed consent from participants to utilise their data within the research.

- Participants’ identities should not be revealed unless agreed. Instead, use anonymised names such as ‘Participant A’.

- See below for templates to outline your research and gain informed consent.

How can I design effective questions?

- Begin by making a list of the types of data you’re aiming to find. See Davies and Hughes (2014, pp. 104-105) suggested aspects below.

- Facts: Do you want to gather any basic facts about the participant e.g. how long they have been working in their field?

- Knowledge: Do you want to gain their knowledge about the topic? (e.g. What does [insert term/topic] mean to them?)

- Attitudes/beliefs, feelings: Do you want to capture their attitude, beliefs or feelings toward a topic?

- Past events: Would you like them to give examples of past projects or experiences?

- Things to avoid when writing questions: ambiguity (being unclear), making assumptions, leading language, being overly complex or asking too many questions (Blaxter, Hughes and Tight, 2001, p. 182).

- You’ll find examples of different question types in the downloadable guide below.

Reference List

Arksey, H. and Knight, P.T. (1999) Interviewing for social scientists: An introductory resource with examples. COME BACK TO!

Blaxter, L., Hughes, C. and Tight, M. (2001) How to research. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Davies, M.B. and Hughes, N. (2014) Doing a successful research project: Using qualitative or quantitative methods. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Denscombe, M. (2014) The good research guide. 5th edn. Maidenhead: Open University.

Kara, H. (2020) Creative research methods: A practical guide. Bristol: Policy Press.

Krueger, R. A. (1998) Developing questions for focus groups. London: SAGE.